35.3 Fighting Infectious Disease

How do vaccines and externally produced antibodies fight disease?

How do vaccines and externally produced antibodies fight disease? How do public health measures and medications fight disease?

How do public health measures and medications fight disease? Why have patterns of infectious diseases changed?

Why have patterns of infectious diseases changed?

vaccination

active immunity

passive immunity

Venn Diagram Make a Venn diagram that compares and contrasts active and passive immunity.

THINK ABOUT IT More than 200 years ago, English physician Edward Jenner noted that milkmaids who contracted a mild disease called cowpox didn't develop smallpox. At the time, smallpox was a widespread disease that killed many people. Jenner wondered, could people be protected from smallpox by deliberately infecting them with cowpox?

Acquired Immunity

How do vaccines and externally produced antibodies fight disease?

How do vaccines and externally produced antibodies fight disease?

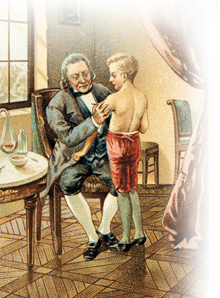

Jenner performed a bold experiment. He put fluid from a cowpox patient's sore into a small cut he made on the arm of a young boy named James Phipps. As expected, James developed mild cowpox. Two months later, Jenner injected James with fluid from a smallpox infection. Fortunately for James (and Jenner!), the boy didn't develop smallpox. His cowpox infection had protected him from smallpox infection. Ever since that time, the injection of a weakened form of a pathogen, or of a similar but less dangerous pathogen, to produce immunity has been known as a vaccination. The term comes from the Latin word vacca, meaning “cow,” as a reminder of Jenner's work.

Active Immunity Today, we understand how vaccination works.  Vaccination stimulates the immune system with an antigen. The immune system produces memory B cells and memory T cells that quicken and strengthen the body's response to repeated infection. This kind of immunity, called active immunity, may develop as a result of natural exposure to an antigen (fighting an infection) or from deliberate exposure to the antigen (through a vaccine).

Vaccination stimulates the immune system with an antigen. The immune system produces memory B cells and memory T cells that quicken and strengthen the body's response to repeated infection. This kind of immunity, called active immunity, may develop as a result of natural exposure to an antigen (fighting an infection) or from deliberate exposure to the antigen (through a vaccine).

Passive Immunity Disease can be prevented in another way.  Antibodies produced against a pathogen by other individuals or animals can be used to produce temporary immunity. If externally produced antibodies are introduced into a person's blood, the result is passive immunity. Passive immunity lasts only a short time because the immune system eventually destroys the foreign antibodies.

Antibodies produced against a pathogen by other individuals or animals can be used to produce temporary immunity. If externally produced antibodies are introduced into a person's blood, the result is passive immunity. Passive immunity lasts only a short time because the immune system eventually destroys the foreign antibodies.

Passive immunity can also occur naturally or by deliberate exposure. Natural passive immunity occurs when antibodies are passed from a pregnant woman to the fetus (across the placenta), or to an infant through breast milk. For some diseases, antibodies from humans or animals can be injected into an individual. For example, people who have been bitten by rabid animals are injected with antibodies for the rabies virus.

FIGURE 35–14 Jenner Vaccinating James Phipps

Table of Contents

- Formulas and Equations

- Applying Formulas and Equations

- Mean, Median, and Mode

- Estimation

- Using Measurements in Calculations

- Effects of Measurement Errors

- Accuracy

- Precision

- Comparing Accuracy and Precision

- Significant Figures

- Calculating With Significant Figures

- Scientific Notation

- Calculating With Scientific Notation

- Dimensional Analysis

- Applying Dimensional Analysis