The Molecular Cause of Transformation In 1944, a group of scientists at the Rockefeller Institute in New York decided to repeat Griffith's work. Led by the Canadian biologist Oswald Avery, the scientists wanted to determine which molecule in the heat-killed bacteria was most important for transformation. They reasoned that if they could find this particular molecule, it might reveal the chemical nature of the gene.

Avery and his team extracted a mixture of various molecules from the heat-killed bacteria. They carefully treated this mixture with enzymes that destroyed proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and some other molecules, including the nucleic acid RNA. Transformation still occurred. Clearly, since those molecules had been destroyed, none of them could have been responsible for transformation.

Avery's team repeated the experiment one more time. This time, they used enzymes that would break down a different nucleic acid—DNA. When they destroyed the DNA in the mixture, transformation did not occur. There was just one possible explanation for these results: DNA was the transforming factor.  By observing bacterial transformation, Avery and other scientists discovered that the nucleic acid DNA stores and transmits genetic information from one generation of bacteria to the next.

By observing bacterial transformation, Avery and other scientists discovered that the nucleic acid DNA stores and transmits genetic information from one generation of bacteria to the next.

Bacterial Viruses

What role did bacterial viruses play in identifying genetic material?

What role did bacterial viruses play in identifying genetic material?

Scientists are a skeptical group. It usually takes several experiments to convince them of something as important as the chemical nature of the gene. The most important of the experiments relating to the discovery made by Avery's team was performed in 1952 by two American scientists, Alfred Hershey and Martha Chase. They collaborated in studying viruses—tiny, nonliving particles that can infect living cells.

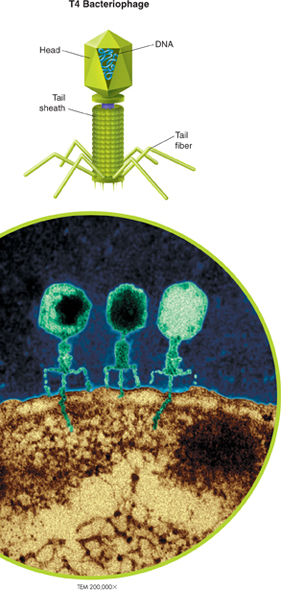

Bacteriophages A bacteriophage is a kind of virus that infects bacteria. When a bacteriophage enters a bacterium, it attaches to the surface of the bacterial cell and injects its genetic information into it, as shown in Figure 12–2. The viral genes act to produce many new bacteriophages, which gradually destroy the bacterium. When the cell splits open, hundreds of new viruses burst out.

FIGURE 12–2 Bacteriophages A bacteriophage is a type of virus that infects and kills bacteria. The top diagram shows a bacteriophage known as T4. The micrograph shows three T2 bacteriophages (green) invading an E. coli bacterium (gold). Compare and Contrast How large are viruses compared with bacteria?

Table of Contents

- Formulas and Equations

- Applying Formulas and Equations

- Mean, Median, and Mode

- Estimation

- Using Measurements in Calculations

- Effects of Measurement Errors

- Accuracy

- Precision

- Comparing Accuracy and Precision

- Significant Figures

- Calculating With Significant Figures

- Scientific Notation

- Calculating With Scientific Notation

- Dimensional Analysis

- Applying Dimensional Analysis