Speciation in Darwin's Finches

What is a current hypothesis about Galápagos finch speciation?

What is a current hypothesis about Galápagos finch speciation?

Recall that Peter and Rosemary Grant spent years on the Galápagos islands studying changes in finch populations. The Grants measured and recorded anatomical characteristics such as beak length of individual medium ground finches. Many of the characteristics appeared in bell-shaped distributions typical of polygenic traits. As environmental conditions changed, the Grants documented directional selection among the traits. When drought struck the island of Daphne Major, finches with larger beaks capable of cracking the thickest seeds survived and reproduced more often than others. Over many generations, the proportion of large-beaked finches increased.

We can now combine these studies by the Grants with evolutionary concepts to form a hypothesis that answers a question: How might the founder effect and natural selection have produced reproductive isolation that could have led to speciation among Galápagos finches?  According to this hypothesis, speciation in Galápagos finches occurred by founding of a new population, geographic isolation, changes in the new population's gene pool, behavioral isolation, and ecological competition.

According to this hypothesis, speciation in Galápagos finches occurred by founding of a new population, geographic isolation, changes in the new population's gene pool, behavioral isolation, and ecological competition.

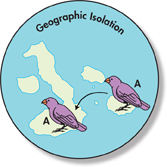

FIGURE 17–13

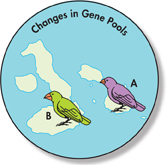

FIGURE 17–14

FIGURE 17–15

Founders Arrive Many years ago, a few finches from South America—species M—arrived on one of the Galápagos islands, as shown in Figure 17–13. These birds may have gotten lost or been blown off course by a storm. Once on the island, they survived and reproduced. Because of the founder effect, allele frequencies of this founding finch population could have differed from allele frequencies in the original South American population.

Geographic Isolation The island's environment was different from the South American environment. Some combination of the founder effect, geographic isolation, and natural selection enabled the island finch population to evolve into a new species—species A. Later, a few birds from species A crossed to another island. Because these birds do not usually fly over open water, they move from island to island very rarely. Thus, finch populations on the two islands were geographically isolated from each other and no longer shared a common gene pool.

Changes in Gene Pools Over time, populations on each island adapted to local environments. Plants on the first island may have produced small, thin-shelled seeds, whereas plants on the second island may have produced larger, thick-shelled seeds. On the second island, directional selection would have favored individuals with larger, heavier beaks. These birds could crack open and eat the large seeds more easily. Thus, birds with large beaks would be better able to survive on the second island. Over time, natural selection would have caused that population to evolve larger beaks, forming a distinct population, B, characterized by a new phenotype.

Table of Contents

- Formulas and Equations

- Applying Formulas and Equations

- Mean, Median, and Mode

- Estimation

- Using Measurements in Calculations

- Effects of Measurement Errors

- Accuracy

- Precision

- Comparing Accuracy and Precision

- Significant Figures

- Calculating With Significant Figures

- Scientific Notation

- Calculating With Scientific Notation

- Dimensional Analysis

- Applying Dimensional Analysis