Case Study #1: Atmospheric Ozone

Between 20 and 50 kilometers above Earth's surface, the atmosphere contains a relatively high concentration of ozone called the ozone layer. Ozone at ground level is a pollutant, but the natural ozone layer absorbs harmful ultraviolet (UV) radiation from sunlight. Overexposure to UV radiation is the main cause of sunburn. It also can cause cancer, damage eyes, and lower resistance to disease. And intense UV radiation can damage plants and algae. By absorbing UV light, the ozone layer serves as a global sunscreen.

The following is an ecological success story. Over four decades, society has recognized a problem, identified its cause, and cooperated internationally to address a global issue.

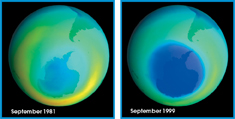

Recognizing a Problem: “Hole” in the Ozone Layer Beginning in the 1970s, satellite data revealed that the ozone concentration over Antarctica was dropping during the southern winter. An area of lower ozone concentration is commonly called an ozone hole. It isn't really a “hole” in the atmosphere, of course, but an area where little ozone is present. For several years after the ozone hole was first discovered, it grew larger and lasted longer each year. Figure 6–24 shows the progression from 1981 to 1999. The darker blue color in the later image indicates that the ozone layer had thinned since 1981.

FIGURE 6–24 The Disappearing Ozone

Researching the Cause: CFCs In 1974 a research team led by Mario Molina, F. Sherwood Rowland, and Paul J. Crutzen demonstrated that gases called chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) could damage the ozone layer. This research earned the team a Nobel Prize in 1995. CFCs were once widely used as propellants in aerosol cans; as coolant in refrigerators, freezers, and air conditioners; and in the production of plastic foams.

FIGURE 6–25 CFC-Containing Refrigerators

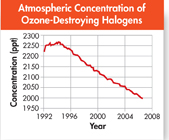

Changing Behavior: Regulation of CFCs Once the research on CFCs was published and accepted by the scientific community, the rest was up to policymakers—and in this case, their response was tremendous. Following the recommendations of ozone researchers, 191 countries signed a major agreement, the Montreal Protocol, which banned most uses of CFCs. Because CFCs can remain in the atmosphere for a century, their effects on the ozone layer are still visible. But ozone-destroying halogens from CFCs have been steadily decreasing since about 1994, as shown in Figure 6–26, evidence that the CFC ban has had positive long-term effects. In fact, current data predict that although the ozone hole will continue to fluctuate in size from year to year, it should disappear for good around the middle of this century.

Table of Contents

- Formulas and Equations

- Applying Formulas and Equations

- Mean, Median, and Mode

- Estimation

- Using Measurements in Calculations

- Effects of Measurement Errors

- Accuracy

- Precision

- Comparing Accuracy and Precision

- Significant Figures

- Calculating With Significant Figures

- Scientific Notation

- Calculating With Scientific Notation

- Dimensional Analysis

- Applying Dimensional Analysis