Case Study #2: North Atlantic Fisheries

From 1950 to 1997, the annual world seafood catch grew from 19 million tons to more than 90 million tons. This growth led many to believe that the fish supply was an endless, renewable resource. However, recent dramatic declines in commercial fish populations have proved otherwise. This problem is one society is still working on.

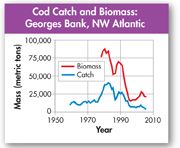

Recognizing a Problem: More Work, Fewer Fish The cod catch has been rising and falling over the last century. Some of that fluctuation has been due to natural variations in ocean ecosystems. But often, low fish catches resulted when boats started taking too many fish. From the 1950s through the 1970s, larger boats and high-tech fish-finding equipment made the fishing effort both more intense and more efficient. Catches rose for a time but then began falling. The difference this time, was that fish catches continued to fall despite the most intense fishing effort in history. As shown in Figure 6–27, the total mass of cod caught has decreased significantly since the 1980s because of the sharp decrease of cod biomass in the ocean. You can't catch what isn't there.

Researching the Cause: Overfishing Fishery ecologists gathered data including age structure and growth rates. Analysis of these data showed that fish populations were shrinking. By the 1990s, cod and haddock populations had dropped so low that researchers feared these fish might disappear for good. It has become clear that recent declines in fish catches were the result of overfishing, as seen in Figure 6–28. Fish were being caught faster than they could be replaced by reproduction. In other words, the death rates of commercial fish populations were exceeding birth rates.

FIGURE 6–28 Overfishing

Changing Behavior: Regulation of Fisheries The U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service used its best data to create guidelines for commercial fishing. The guidelines specified how many fish of what size could be caught in U.S. waters. In 1996, the Sustainable Fisheries Act closed certain areas to fishing until stocks recover. Other areas are closed seasonally to allow fish to breed and spawn. These regulations are helping some fish populations recover, but not all. Aquaculture—the farming of aquatic animals—offers a good alternative to commercial fishing with limited environmental damage if properly managed.

Overall, however, progress in restoring fish populations has been slow. International cooperation on fisheries has not been as good as it was with ozone. Huge fleets from other countries continue to fish the ocean waters outside U.S. territorial waters. Some are reluctant to accept conservation efforts because regulations that protect fish populations for the future cause job and income losses today. Of course, if fish stocks disappear, the result will be even more devastating to the fishing industry than temporary fishing bans. The challenge is to come up with sustainable practices that ensure the long-term health of fisheries with minimal short-term impact on the fishing industry. Exactly how to meet that challenge is still up for debate.

FIGURE 6–29 Aquaculture

Table of Contents

- Formulas and Equations

- Applying Formulas and Equations

- Mean, Median, and Mode

- Estimation

- Using Measurements in Calculations

- Effects of Measurement Errors

- Accuracy

- Precision

- Comparing Accuracy and Precision

- Significant Figures

- Calculating With Significant Figures

- Scientific Notation

- Calculating With Scientific Notation

- Dimensional Analysis

- Applying Dimensional Analysis