Friction

All moving objects are subject to friction, a force that opposes the motion of objects that touch as they move past each other. Without friction, the world would be a very different place. In a frictionless world, every surface would be more slippery than a sheet of ice. Your food would slide off your fork. Walking would be impossible. Cars would slide around helplessly with their wheels spinning.

Friction acts at the surface where objects are in contact. Note that “in contact” includes solid objects that are directly touching one another as well as objects moving through a liquid or a gas.  There are four main types of friction: static friction, sliding friction, rolling friction, and fluid friction.

There are four main types of friction: static friction, sliding friction, rolling friction, and fluid friction.

Static Friction

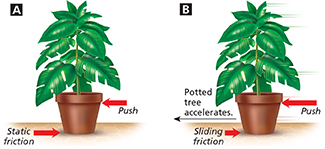

Imagine trying to push a large potted tree across a patio. Although you apply force to the pot by pushing on it, you can't get the pot to move. As shown in Figure 5A, the force of static friction opposes your push. Static friction is the friction force that acts on objects that are not moving. Static friction always acts in the direction opposite to that of the applied force.

You experience static friction every time you take a step. As you push off with each step, static friction between the ground and your shoe keeps your shoe from sliding.

Sliding Friction

With the help of a friend, you push on the pot with enough force to overcome the static friction. The pot slides across the patio as shown in Figure 5B. Once the pot is moving, static friction no longer acts on it. Instead, a smaller friction force called sliding friction acts on the sliding pot. Sliding friction is a force that opposes the direction of motion of an object as it slides over a surface. Because sliding friction is less than static friction, less force is needed to keep an object moving than to start it moving.

Figure 5 Different types of friction act on moving and nonmoving objects.

A Static friction acts opposite the direction of the force you apply to move the plant. The potted tree does not move. B When you push with more force, the potted tree begins to slide. Sliding friction acts to oppose the direction of motion.